Is there data available before the onset of the crisis, on the level of trust by the population of the two primarily English-speaking regions in the State/public administration, the political system and institutions, and on their sense of national identity (belonging)? And data on their subsequent perception of what caused the crisis?

Data Source: Governance, Peace & Security Module Data (GPS-SHaSA),

Collected under Cameroon’s 4th National Household Survey (ECAM-4), National Institute of Statistics, 2014

Data Analysis: Mireille RAZAFINDRAKOTO & François ROUBAUD, Sous la crise anglophone au Cameroun: frustrations politiques et défiance à l’égard des autorités publiques, Document de Travail IRD et UMR DIAL, Université Paris-Dauphine, décembre 2018, 22 pp..

Data Explanation:

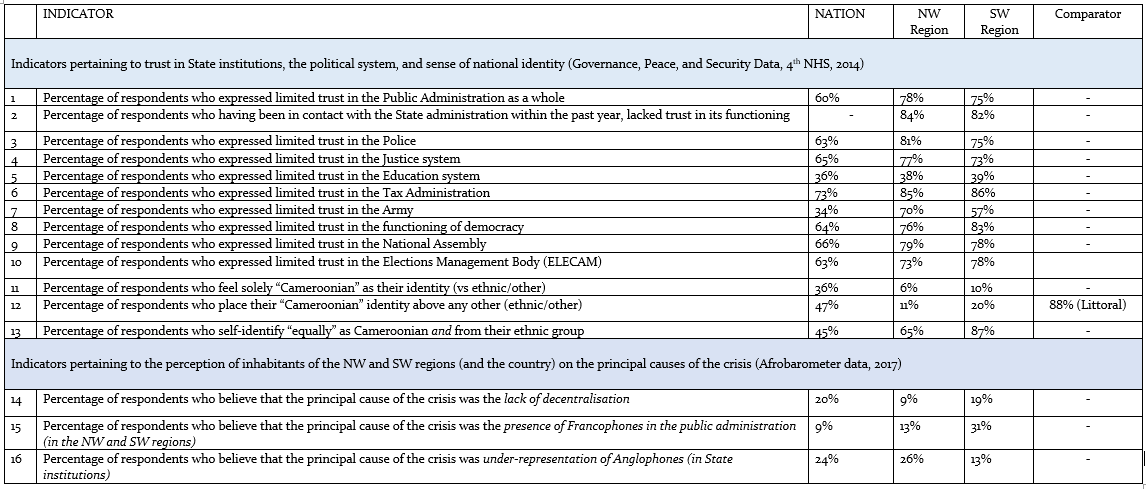

Relying principally on the above-mentioned data analysis, the general trend that can be discerned is that in 2014, just before the start of the crisis, there was quite a marked distinction between the NW and SW regions and the rest of the country, in terms of the former’s lack of trust in the State administration, the political system, and its institutions; and that they harboured the most nuanced views (amongst regions of the country) in terms of their self-identification with a single (national) identity. Across the board, for all indicators in this category, in 2014, the NW and SW regions expressed the most critical views, and stood out with levels of dissatisfaction significantly higher than the national average.

The proportion of survey respondents who expressed limited trust in the public administration viewed as a whole, was much higher in the 2 regions (3/4) than the national average (2/3). And unlike the situation in the 8 other regions of the country, those survey respondents who had recently interacted with the public administration were more distrustful of the said administration than those who had not interacted with it. Key institutions for the exercise of State power (the Police, Justice system, the Tax Administration, and the Army) enjoyed only a limited degree of trust in these 2 regions, which was significantly lower than the national average. While the degree of trust in the educational system was about the same in the 2 regions as the national average, these regions were the most critical in their perception of the educational system.

The majority of survey respondents in the two regions had little trust in the functioning of the democratic system as a whole (mechanisms for political representation through elected officials) and of its constituent institutions, notably the National Assembly and the election management body. Here again, the levels of trust were much lower than the national average. It is telling that the SW region, while being the best performer nationally on poverty alleviation (18.2% poverty incidence, per 4th NHS, 2014) was also the most critical as to the functioning of democracy (83% of respondents dissatisfied, per GPS-SHaSA data, 2014).

La proportion de répondants exprimant une confiance limitée à l’égard de l’administration dans son ensemble était nettement plus élevée dans ces 2 régions (les 3/4) que la moyenne nationale (les 2/3). Et contrairement à d’autres régions, ceux des répondants qui ont effectivement eu un contact récent avec l’administration en sortaient moins confiant que ceux qui n’ont pas eu de contact. Certaines institutions clefs d’exercice du pouvoir public (la Police, la Justice, l’administration fiscale, l’Armée) ne bénéficiaient dans ces 2 régions que d’une confiance limitée, largement en dessous de la moyenne nationale. Si la confiance à l’égard du système éducatif était proche de la moyenne nationale, ces 2 régions étaient néanmoins les deux les plus critiques dans ce domaine.

On the (subjective) sense of belonging to a larger grouping (ethnic group, Nation), these 2 regions stood out as those in which the respondents felt “equally attached” to their subnational trait (ethnic) as to their national trait (Cameroonian). Respondents also rarely self-identified exclusively with their national trait. The above-mentioned data leads the authors of the data analysis cited above, to conclude that a profound sense of dissatisfaction with the public administration, and with political institutions, was the key trait that the NW and SW regions had in common, before the onset of the crisis.

The indicators pertaining to the perception of inhabitants of the NW and SW regions (and the country) on the principal causes of the crisis, evaluated during an Afrobarometer survey of 2017, reveal the following findings. Survey respondents in the SW region held about the same view as their counterparts nationally, that the lack of decentralisation was a major cause of the crisis (around 20%); however much fewer respondents in the NW region ascribed the crisis’ cause to this factor (9%). Twice as many survey respondents in the NW region than in the SW region (26% versus 13%) felt the crisis’ principal cause was something more pernicious than a simple delay in implementing decentralisation: they attributed it to the under-representation of Anglophones in public institutions.

It is also striking that a very high percentage of survey respondents in the SW region (31% as against 13% in the NW region) felt that the principal cause of the crisis was the very high numbers of Francophones in the public administration (in the NW and SW regions). This is an important observation, given the SW region’s better socio-economic conditions and its higher degree of urbanisation, which probably felt more directly, the increase in Francophones in the public administration within the region.