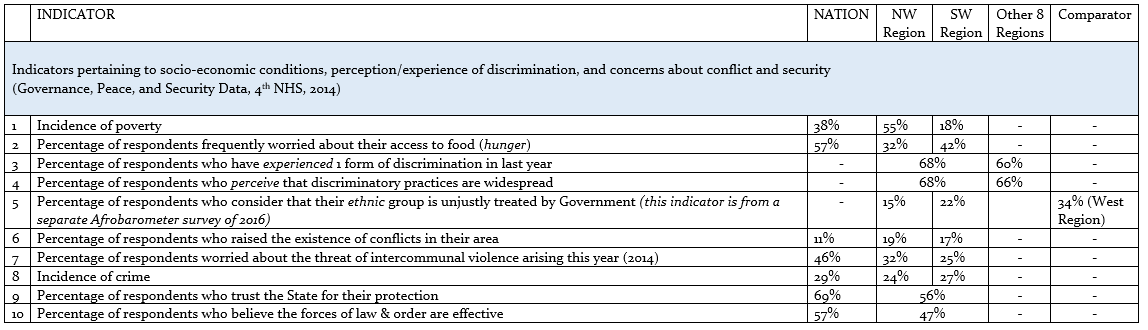

What was the objective socio-economic situation of the NW and SW regions before the onset of the crisis in 2016? Did these regions rank much worse in development indicators, compared to other regions of the country?

Data Source: Governance, Peace & Security Data (GPS-SHaSA),

Collected under Cameroon’s 4th National Household Survey (ECAM-4), National Institute of Statistics, 2014

Data Analysis: Mireille RAZAFINDRAKOTO & François ROUBAUD, Sous la crise anglophone au Cameroun: frustrations politiques et défiance à l’égard des autorités publiques, Document de Travail IRD et UMR DIAL, Université Paris-Dauphine, décembre 2018, 22 pp.

Data Explanation:

Relying principally on the above-mentioned data analysis, a number of trends can be discerned. Firstly, that (adverse) socio-economic conditions in these two regions cannot on their own be advanced as having triggered the crisis, for the two regions (NW and SW) had diametrically opposed socio-economic fortunes at the start of the crisis. (See the separate question about poverty incidence trends in the 2 regions). Secondly, that on most of the indicators tested under this rubric, such as experiences of discrimination, risk of conflict, and insecurity, there was not (in 2014, just before the start of the crisis), a marked or significant difference between the perception of citizens in the NW and SW regions, and those in the rest of the country.

On the problem of discrimination, the percentage of survey respondents who indicated having personally suffered from discrimination, and those who believed that discrimination was a significant and pervasive problem in the country, was about the same in the NW and SW regions, as among Cameroonians in all the other regions. This points to the fact that concerns about discrimination (e.g. ethnic/regional) were rather a nationwide phenomenon or problem, and not negative treatment experienced solely by the residents of these two regions. In 2014, the percentage of survey respondents who believed that their ethnic group was being unjustly treated by the State authorities, was low in the NW and SW regions compared to other regions, and had even dropped compared to perceptions of such unjust treatment some years earlier.

It should however be pointed out that for survey respondents in the predominantly Anglophone NW and SW regions, unfavourable treatment by the public administration on account of that trait (being primarily English-speaking) may not necessarily be perceived as “discrimination” (as between population categories in the NW-SW regions), but would surface rather as a shared mistrust by a large part of the population, towards the public administration. Additionally, the survey did not target eliciting the perception/experience of persons from the NW/SW or Anglophones residing outside those 2 regions, where they are potentially most exposed to being at a disadvantage as a result of their primary official language.

The percentage of respondents in the NW and SW who raised the issue of conflicts in their localities, or who expressed concern about the occurrence of inter-communal conflicts, was about the same as, or even lower than, the national average. The (objective) incidence of crime in the two regions was also lower than the national average. In the NW and SW regions, the percentage of respondents who trusted the State for their protection, and who believed the forces of law and order were effective, was lower than the national average. However, they constituted nearly half (50%) of respondents in the two regions.